Great Horned Owl – True Omnivore Predator

Great horned owls consume a greater diversity of prey than any other North American owl. Their diet includes all kinds of things: every type of vertebrate mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians and and a wide range of invertebrates: earthworms, crayfish, scorpions, centipedes and both larval and adult insects; so just about anything. These prey range in size from grasshopper to great blue herons! However, although there is much geographical, seasonal and variation by year in prey, mammals dominate the menu, being about 90 percent of the owl’s diet in most areas. Birds generally make up only a tenth of the diet, but the hunters occasionally identify a source of avian prey that can be easily exploited and focus their hunting attention there. Great horned owls living on Washington State’s Protection Island dine almost exclusively on rhinoceros auklets in the summer. An estimated 17,000 pairs of these burrow-nesting seabirds nest annually on the 368 acre national wildlife refuge, which is also home to a number of other bird species but few mammals, except for some shrews and the odd chipmunk. Researchers found 129 great horned owl pellets on the island over two summers, 112 contained only auklet remains and another 8 contained a mix of auklet and other bird bones. Mammal remains were completely absent. The kind of opportunism exhibited by the Protection Island owls is likely responsible for this species’ undeserved reputation as a ruthless poultry killer. An individual owl that discovers a poorly secured chicken coop might well return nightly for an easy meal, especially if there is a local scarcity of mammals to prey on, but the majority of the owls executed for this alleged crime have been innocent victims. Fortunately such killings are now rare, as well as illegal.

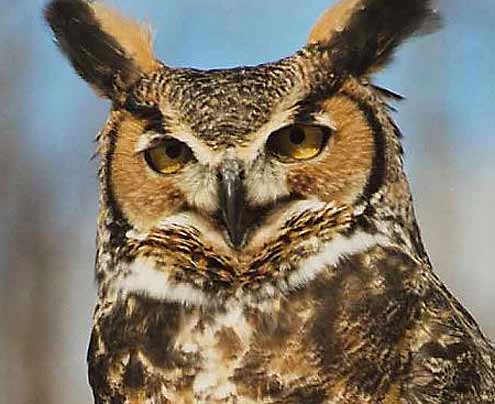

Great horned owls are distinguished by their large size, with a length of 18-25 inches (46-63 cm), bulky shape, prominent ear tufts, large yellow eyes and white bib. Females are noticeably larger than males. Plumage coloring ranges from grayish to gray-brown to buffy brown. The darkest individuals are found in humid coastal areas and the lightest in the arid sub-arctic Prairies, Great Plains and American Southwest. The head and back are mottled whitish, dusky and dark brown. The paler underparts are mostly barred dark brown, except for the black-blotched upper chest and the bib – an immaculate white crescent across the throat. A narrow black border encircles the outer edges of the facial disk. The legs and feet are feathered.

The primary song of the bird is a series of deep, mellow, far-carrying hoots, with considerable variability in length and number; generally there are three to eight hoots in each set, but sometimes a single hoot is repeated at irregular intervals. Male vocalizations are more prolonged and elaborate, usually lower-pitched. During courtship mated pairs often synchronize their territorial singing. This owl’s diverse array of calls includes piercing screams (most commonly uttered by females, especially when defending the nest), sharp whistles (for contact with fledglings) and short, barking alarm notes, as well as chuckles, growls, hisses, squawks, cat-like meows, soft coos and quavering cries.

Although mainly nocturnal, great horned owls sometimes hunt during daylight hours when the going is a little tough, such as when they are feeding young. Their varied roosts include tree foliage (coniferous or deciduous), thick brush, tree cavities, cliff ledges and buildings. Males typically use a single preferred roost site during nesting and change roosts from day to day during the non-breeding season.

The great horned owl has a more extensive North American breeding range than any other owl, encompassing nearly all of Canada and the United States, from the arctic tundra south, and much of Mexico, except parts of the humid southeast. It tends to avoid the Appalachian and Rocky mountains and the Mojave and Sonoran deserts. They also inhabit parts of Central and South America.

Habitats occupied by this species are extremely diverse. The minimum requirements are suitable nesting and roosting trees and sufficiently large hunting areas that are relatively open but with at least a few scattered perches, such as open woodlands, wetlands, grasslands, clearings, farm fields or pastures. The trees may be deciduous, coniferous or a mix of both, and elevations range from sea level to about 13,200 feet (4,000 m). Great horned owls occasionally take up residence in cities, especially around parks and golf courses.

As mentioned earlier, these opportunistic hunters kill a wide range of vertebrate and invertebrate prey but focus mainly on rabbits, hares, rodents and water-fowl. The owls hunt primarily from perches (including trees, tall shrubs, rock out-crops, cliff ledges, bridges, poles and buildings) in open areas. They sometimes move on foot when hunting small mammals or invertebrates in grassy areas or other suitable habitat. They may also forage by flying low across open areas such as grasslands or sagebrush habitats.

Although great horned owls are solitary outside the breeding season, members of a pair often share the same territory year-round and may mate for life. They nest mostly in stick nests made by other birds. They also regularly use cliff ledges and rock outcrops, especially in arid areas, as well as tree cavities and hollow broken-topped trunks. Unusual sites include abandoned buildings, bridge beams and the ground. They readily use nest baskets or platforms. The usual clutch size is two, increasing to a maximum of five when food is abundant. Laying dates vary widely with latitude – in Florida, rare very early clutches have been found in late November; in northern areas, laying is sometimes not completed until mid-May. The eggs are incubated for 3o to 37 days and the young leave the nest about six weeks after hatching. Fledglings remain with their parents through summer and gradually disperse before the next breeding season.

Although great horned owls are nonmigratory, members of northern populations periodically move long distances south in winter, particularly when snowshoe hare populations crash. The longest known journey of this type is 1,235 miles (2,058 km), from Alberta to western Illinois.

The owl populations are thought to be healthy in most areas, but long-term trends are not well-known. Densities are naturally low, with numbers fluctuating in relation to prey populations where these are cyclic. While illegal shooting, traps, vehicle collisions and electrocution kill many individuals, their impact on populations may be minimal. These owls adapt well to habitat change, provided nest sites are available They may benefit from clear-cut logging in densely forested areas.